In a few generations, balloons might become a thing of the past (Matthew Faitz)

Buy a balloon at the zoo. Let it go and watch it shrink down to a tiny dot and then disappear into the stratosphere. Either that balloon will fly too high and shatter, or it will slowly leak out its lighter-than-air contents. Either way, eventually the helium inside the balloon will escape and make its way out of the atmosphere. The earth is literally leaking its helium into outer space.

That’s the future of most of the world’s helium over the next 100 years, scientists say. Such is the fate of a gas lighter than air — Earth’s gravitational pull just can’t hold it.

The earth’s crust emits some helium, but the atmosphere loses it fast. The helium in our atmosphere is pretty stable at 5.2 parts per million. Extracting that small amount from the air would be very expensive. The helium that you can buy and use is extracted from natural gas reserves, mostly in the United States. After it’s extracted, and used — be it for party balloons, or MRI machines, or rockets, or to grow crystals for silicon wafers — most of it makes its way up, up, and away.

As helium supplies start to dwindle, the prices have already started to rise, and party balloons are taking a back-seat to the more serious applications. A hundred years down the line, a party balloon might be about as precious as a gold ring.

Despite the fact that science has known about the impending helium scarcity for decades, it’s only made the news in the past five years. Why that is has a lot to do with helium’s complicated political history in the United States.

How Did We Get Here?

Helios’ son joy riding on his father’s chariot (Nicolas Bertin)

In 1868, the existence of helium was first detected as a line in the spectral signature of sunlight in a solar eclipse. It was named “helium” after the Greek god Helios, who drew the sun across the sky every day behind his golden chariot. It was first isolated by Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay in 1895. In the same year, Swedish chemists Per Teodor Cleve and Abraham Langet discovered the gas independently, and collected enough of it to determine its atomic number: 2.

Helium is present in the sun’s energy spectrum because it’s a giant ball of hydrogen gas and helium gas. It has such gravitational pull that, at the center, hydrogen atoms (which have one proton) are fused together and become helium atoms (which have two protons). This process is known as nuclear fusion, and it gives off energy — a lot of it. Enough that we can see the sun’s light, and feel its heat, from almost 100 million miles away. We don’t get any of its helium, though. And the helium first isolated by scientists was the byproduct of dissolving the mineral uraninite in acid, a process that was both radioactive and expensive.

Then in 1903, an oil rig in Kansas produced a geyser of initially disappointingly non-flammable gas. The gas was taken back to a lab for analysis and determined to be 1.8% helium — a much higher concentration than was found in the atmosphere. Engineers started examining gas from wells across the country, and as a result scientists wrote in 1906, “helium is no longer a rare element, but a common element, existing in goodly quantity for uses that are yet to be found for it.”

Why helium is much better than hydrogen for airships

Now that it was common, helium was a natural choice to fill rubber balloons and zeppelins, which had previously been filled with the similarly buoyant but highly combustible hydrogen. But it was not at all common outside the United States, and the government sought to keep it that way. In 1925, Congress established the United States National Helium Reserve, as a strategic stockpile of helium for military and commercial airships. The 1927 Helium Control Act prohibited helium’s export. As a result, foreign blimps and zeppelins like the Hindenburg were filled with hydrogen, resulting in the infamous disaster.

Other important uses for helium were soon discovered. In addition to being lighter than air, helium has an extremely low boiling point: 4.22 Kelvin, or -452.07 degrees Fahrenheit, the lowest of all the elements. That ends up being very useful, because if you can keep it in a liquid state, you have an excellent coolant. When a liquid boils, it stays at its boiling point so long as it stays liquid — it never gets any hotter. Water never exceeds 212 degrees, and liquid helium never exceeds -452 degrees. Helium started being used to insulate arc welding, and, later, superconductors and nuclear reactors, and in cryogenics. The use of helium as a coolant is the leading use of helium today.

Other uses of helium: The gas is also used to detect containment leaks, starting with The Manhattan Project, as it’s an atomically tiny gas that is also inert (stable), and penetrates leaks very quickly. It also is used by Homeland Security for radiation detection, and in medical imaging technology.

The National Helium Reserve

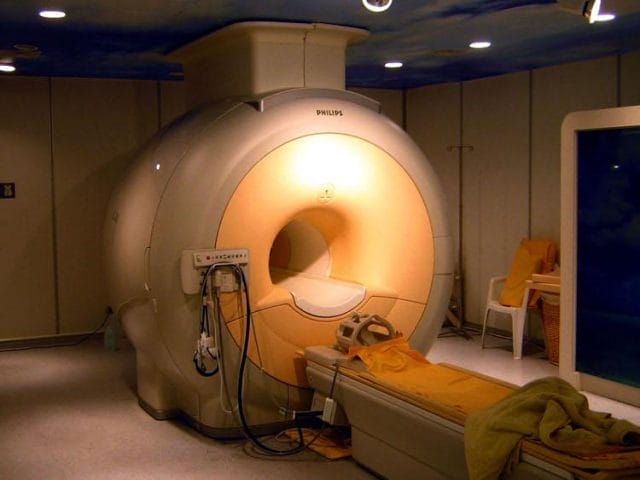

Helium is used to keep the magnets in an MRI machine cool

Although helium-filled airships passed out of use, the National Helium Reserve was preserved and expanded through the latter half of the 20th century because of its continued utility to government operations, most notably the space program and Cold War defense system.

By 1996 there were a billion cubic meters of helium in the Reserve. But it had ceased to look like an industry the government should still be involved with, partially because its finances had been very poorly managed. From the Washington Post:

By 1996 […] the Helium Reserve looked like a waste. Blimps no longer seemed quite so vital to the nation’s defense and, more important, the reserve was $1.4 billion in debt after paying drillers to extract helium from natural gas.

Both Reagan and Clinton promised to do away with the reserve, and in 1996 Congress passed the Helium Privatization Act. The Act ordered the Reserve to sell off its stockpile, starting in 2005, at a formula-driven price — not auctioned off at market rate, and to cease sales and shut down operations by 2015.

Macy’s Day Parade Balloon, by Anthony Quintano

This flooded the market and dramatically drove the price of helium down. And, conservationists argued, dramatically drove consumption up. “As a result of that Act, helium is far too cheap and is not treated as a precious resource,” Nobel laureate Robert Richardson said in 2010. “It’s being squandered.[…] They couldn’t sell it fast enough and the world price for helium gas is ridiculously cheap.” From an article in The Independent:

Professor Richardson believes the price for helium should rise by between 20- and 50-fold to make recycling more worthwhile. Nasa, for instance, makes no attempt to recycle the helium used to clean is rocket fuel tanks, one of the single biggest uses of the gas.

Professor Richardson also believes that party balloons filled with helium are too cheap, and they should really cost about $100 (£75) to reflect the precious nature of the gas they contain

At the current consumption rates, Richardson estimated we would deplete the world’s helium reserves within 100 years.

Also, instead of encouraging private sector participation in helium production, the selling-off of the National Helium Reserve did the exact opposite. Helium became so cheap nobody saw any need, nor profit, in extracting it themselves. As 2015 neared, scientists sounded the alarm that if the National Helium Reserve shut down according to plan, there would be nothing to replace it. The United States is still the world leader in helium production, producing about 70% of the helium in the world, meaning a US shortage could cause worldwide problems.

2013 saw the passage of the Helium Stewardship Act, which allowed the National Helium Reserve to continue operations until 2021, and to sell its helium at auction — creating prices closer to market rate. But not before selling off a large chunk of the Reserve for peanuts.

Data: Bureau of Land Management via Reuters

Helium Today

Even if auctioning eventually solves the pricing problem, it will never change the fact that helium is not a renewable resource. The National Reserve is expected to be depleted by 2020, and even if it isn’t, under the current law it will have to shut down operations in 2021. In the meantime, the world is scrambling to find alternative coolants, levitators, and sources of helium.

“By the end of the decade,” USGS writes in its 2015 report on helium, “international helium extraction facilities are likely to become the main source of supply for world helium users. Expansions to facilities have been completed as planned in Algeria and Qatar.” China also plans on mining helium-3, which is currently mostly manufactured, off the moon.

Different users, encouraged by climbing prices, have begun experimenting with recycling their helium. Depending on how well the synergy of these efforts works, we may be closer to or further from the day in which a bouquet of helium balloons is seen as a frivolous, anachronistic luxury — like ivory piano keys, or silverware actually made out of silver.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list